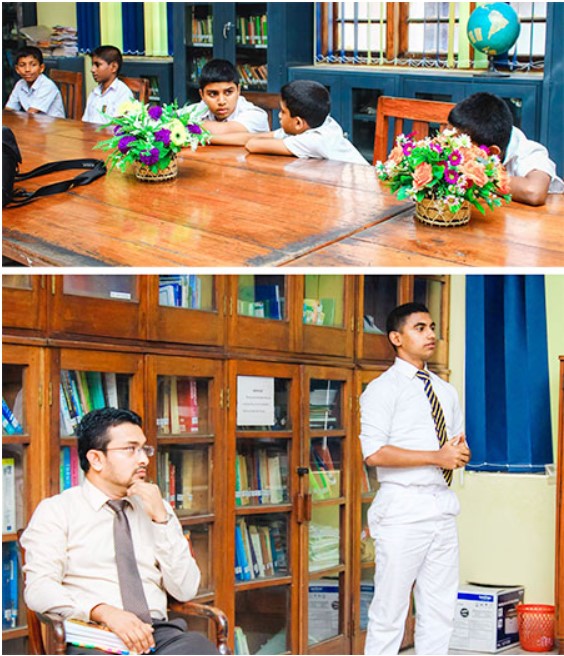

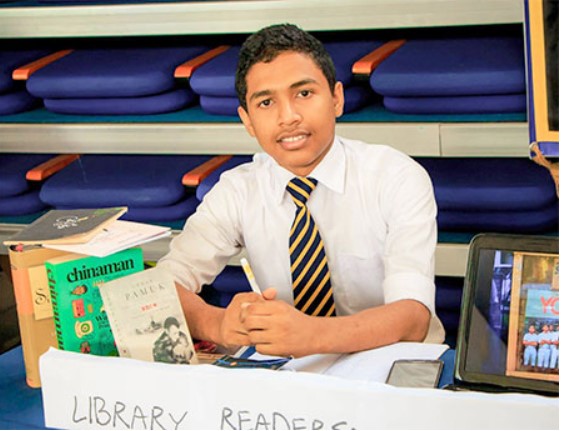

Pix by the Photographic Society of Royal College showing happy moments from LRA’s projects in 2017, 2018 and 2019

Source:Island

Life after your Bachelors can be tough. When I graduated with less than expected results in 2016, the immediate priority was to find a job. I was earning something with my newspaper columns, but those were hardly, if at all, enough. Since I had once worked at my school, as a coach, I decided to return to a school as an office assistant. It would be my first experience at an official post; while the salary did not seem much, for me it felt like riches. Moreover, I had been given the job immediately by the principal. Given my circumstances, her offer was too good to refuse. So I swallowed the bait. I can’t say I regret having doing so.

Even at a school, working at an office can be difficult, though also exhilarating. As a teacher, your responsibility is to your students; your employers come second. As an assistant tied to a desk, sitting in front of a computer screen and typing away, on the other hand, the bosses loom over you from nine to five. While I liked the stability it entailed, I disliked the routines I had to undergo; they felt too tedious, and to stick to them every hour of the day seemed a dismal prospect. Not surprisingly, when I was told of my dismissal barely three months after I got in, I received the news with a sense of relief. Around two months later, responding to a vacancy online, I found another job. Three weeks later I clocked in as an English copywriter at an advertising agency, where I stayed, and worked, for three years.

For financial reasons, I did not let go of writing to newspapers. Though a secondary concern, my columns became a must-do every day. To meet my weekly quota while filling in fulltime work seemed a hefty challenge, but one that I happily endeavoured to go through. Besides, working at the agency brought with it certain advantages: since my articles were usually on the arts, and most of what I wrote on, be it theatre shows and movie screenings, took place in Colombo in the afterhours, it was convenient to attend to them after work. Moreover, since my office was located in the heart of Colombo, it seemed a perfect base for me.

For financial reasons, I did not let go of writing to newspapers. Though a secondary concern, my columns became a must-do every day. To meet my weekly quota while filling in fulltime work seemed a hefty challenge, but one that I happily endeavoured to go through. Besides, working at the agency brought with it certain advantages: since my articles were usually on the arts, and most of what I wrote on, be it theatre shows and movie screenings, took place in Colombo in the afterhours, it was convenient to attend to them after work. Moreover, since my office was located in the heart of Colombo, it seemed a perfect base for me.

I’ve lost count of the people I met and shows I attended over these years. If they seem so far back in time now, it’s because they seemed to occupy another universe then. Young or old, teenage or middle-aged, the people I interviewed projected new perspectives and shed new light on whatever they did in life. Some stayed back longer than the rest. Many faded away. A few, very few, remained in touch. Among those who did, I include a rather interesting set of teenagers that belonged to a rather interesting milieu.

The Library Readers’ Association is the oldest society at Royal College. Established in 1846 as a committee, it became a student association a hundred years later. Though perhaps not as popular as some other clubs, it nevertheless enjoys something of a reputation today, even if the habit of reading is fast drying up among the young. Most of the projects it organises, or used to organise, revolve around newly published books and writers. Its highlight is, or used to be, “Library Week”, a seven-day fiesta of exhibitions, seminars, and film screenings. Apart from these in-house projects, it also organises campaigns to improve libraries across distant parts of the country. All these, incidentally, are kept in line with the society’s vision, which is not just to maintain the school library, but also to promote libraries elsewhere.

What interests me about the association is its membership, or more specifically, the social composition of its membership. This interest goes back all the way to 2017, when I first got to know of the club after its then secretary asked me if I could write on it. I said I could, and soon enough, news of the LRA, as it was called, appeared in the papers. Yet my interest in it went beyond this encounter; as the months passed and as a new board took over in January the following year, it widened. For what it was worth, it continued to pique me.

What interests me about the association is its membership, or more specifically, the social composition of its membership. This interest goes back all the way to 2017, when I first got to know of the club after its then secretary asked me if I could write on it. I said I could, and soon enough, news of the LRA, as it was called, appeared in the papers. Yet my interest in it went beyond this encounter; as the months passed and as a new board took over in January the following year, it widened. For what it was worth, it continued to pique me.

Being educated in English, one invariably embraces and indulges in certain literary tastes to the exclusion of others. My fascination with the LRA stemmed mainly from how different my reading preferences were to those of its members. These differences were in turn linked to the milieu from which the members hailed; not a suburban or urban middle bourgeoisie, as the location of their school would suggest, but a rural middle-class. To put it simply, most of those members entered their school through the Grade Five scholarship; only a tiny fraction (and a very tiny one) hailed from outside this group. I have been told that many, if not most, of those who choose clubs inclined towards literature and the arts also belong to this group, a testament to its presence in such societies, in such institutions.

Undeniable as it may be, it’s not a coincidence that this group continues to exert a profound influence over school societies linked to literature, and not just in public schools. Indeed, the link between such associations and the background of most of their members has, in effect, spilt over to the country’s cultural and literary landscape: most of our writers, lyricists, even actors and scriptwriters, happen to hail from the same milieu as that of Grade Five scholars, rural if not sub-rural, belonging by virtue of their parents’ position in their communities to a twilight world between the city and the village. Since I have written at length on the Sinhala rural middle-class, and how it has shaped and is shaping the social fabric of elite institutions, including public schools, I will concentrate here on its literary preferences.

Most of us – by whom I mean most of the country’s readers, Sinhala speaking and reading – tend to read through certain authors and genres as we grow up. This is true of the readers in the LRA: conversing with many of them, I realised how similar their preferences were: from translations of Russian (Soviet era) texts (a particular favourite: Saba Minisekuge Kathawak, based on Poleyov’s The Story of a Real Man) to Sherlock Holmes rip-offs (done by Chandana Mendis, who gets a new story out in time for the Book Fair every year), they then evolve to more serious original texts (usually, but not always, Martin Wickramasinghe) and occasional translations (Gorky’s Mother as Amma) before indulging in adolescent texts, which bifurcate between glossy romances (Edward Mallawarachchi then, Sujeewa Prasannaarachchi today) and literary award winners, mostly social novels (Mahinda Prasad Masimbula).

If one notices and deplores a uniformity in these tastes and trends, it must be pointed out that uniformity doesn’t necessarily imply staticity: these readers do view literature through a certain framework that conforms to the trajectory I’ve outlined above, yet they indulge in individual preferences as well, which is another way of saying they are eclectic: for the most in Sinhala, though also in English. This may not put them in the same league or class as their English medium counterparts, but it does put them above this league in some respects: thus it was with some amusement that I listened to one member of the association recollecting how frustrated he became with some of his English medium classmates and the books they preferred: “it was always Enid Blyton and Goosebumps, the most juvenile stories you could imagine.” Those from Sinhala speaking backgrounds, by contrast, “read more widely, with a better selection of titles and authors to choose from.”

If one notices and deplores a uniformity in these tastes and trends, it must be pointed out that uniformity doesn’t necessarily imply staticity: these readers do view literature through a certain framework that conforms to the trajectory I’ve outlined above, yet they indulge in individual preferences as well, which is another way of saying they are eclectic: for the most in Sinhala, though also in English. This may not put them in the same league or class as their English medium counterparts, but it does put them above this league in some respects: thus it was with some amusement that I listened to one member of the association recollecting how frustrated he became with some of his English medium classmates and the books they preferred: “it was always Enid Blyton and Goosebumps, the most juvenile stories you could imagine.” Those from Sinhala speaking backgrounds, by contrast, “read more widely, with a better selection of titles and authors to choose from.”

For all intents and purposes, the LRA is still active. Yet the projects it undertakes now seem few and far between, compared with those that marked it out well in the years I associated with it. To me, the link these school clubs and societies throw up, between their literary and cultural bent and their membership, has more or less dovetailed with another link, between the elite position of their schools and the new petite bourgeoisie, the Grade Five scholarship class, changing the social composition of those schools. In that sense these clubs tell us a lot about the changing face of these institutions. They also tell us a lot about the changing face of the country, from not just social and cultural, but also political standpoints. Not unlike the role played by libraries in the unfolding of social processes, hence, these linkages represent exciting fields of study for the anthropologist, as well as the ethnographer.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com