Source:Island

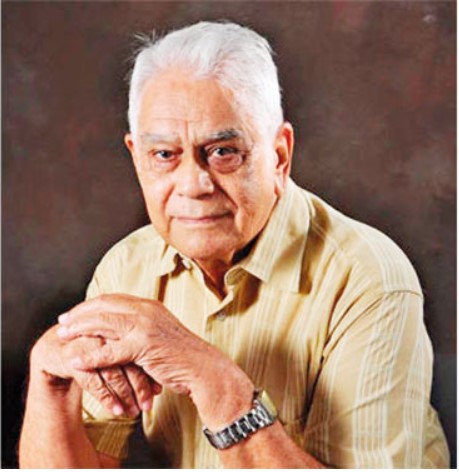

Sujit Canagaretna, in a moving and masterful appreciation of Scott Dirckze, written soon after the latter’s demise in November 2019, has, in the opening paragraph itself, perfectly summed up the multi-faceted man whom he had known from childhood.

Quote. “Humanitarian. Corporate Leader. Entrepreneur. Agriculturist. Raconteur. Citroen Aficionado. Historian. Classical Musicophile. Art Collector. Consummate Host. Explorer. Gentleman. Friend“. Unquote; Elsewhere in the same writing, Sujith refers to Scott as a “Polymath” and “A Renaissance Man”.

I cannot better that description, concise yet all-inclusive. However, on the eve of what would be his 92nd birthday, I would like to share my personal impressions of Scott, as a belated tribute to a man who featured prominently in my life for over half a century, especially as a sounding board in times of uncertainty and, often, shaping my personal direction.For over 50 years, the 4th of July was an important day in my calendar; nothing to do with the Independence Day of the United States of America but because it is Scott Dirckze’s birthday, which he always celebrated in great style. I first attended the celebration in 1968. Since then, if I did miss it, there would have been a very important reason, as it was, literally, a standing but command invitation. Many years ago, the day before the event, I rang him and asked whether I and Malini – my wife – could arrive a bit late as I had another important matter to attend to. He chuckled and said, “Anura, please come early; you can watch the Wimbledon final on my bedroom TV”; a perfect example of Scott’s droll humour! He was all too well aware of my passion for tennis. At that time, he was Chairman of George Steuart & Co, and I was a senior manager of the company.When Malini and I got married in 1971, I had no second choice as my attesting witness. In fact, the two of us were driven away from the function in his beloved, blue and grey Citroen ID 19, chauffeured by his then driver, Dhanapala. At our daughter, Mihirini’s wedding twenty-five years later, Scott again did the honours as her witness. He was deeply touched that we made the request, but it was simply a measure of both our respect and affection for the man.

I first met Scott in 1967, a little over a year after I left school, for me a time of uncertainty and rootlessness. My friend, the late Trevor Roosmale-Cocq, then an estate executive at George Steuarts and later its Managing Director, decided that I needed sane and mature counseling. So, he took me to the man he respected most.

That first image of Scott, wearing a Thai batik shirt and cream slacks, seated on a divan below the large painting of Weligama Bay, in the simply but tastefully appointed sitting room of his modest Park Road residence, is still very vivid and framed him in my mind for the rest of our relationship. To mask my nervousness at meeting a man of obvious importance, a director of the most prestigious estate agency house in the country, I ostentatiously lit a cigarette and helped myself generously to his whiskey. But I shall never forget Scott’s unaffected friendliness and how quickly he put me at ease.

Scott was both practical and kind in his advice. Citing himself as an example, he explained what he considered to be the total uselessness of his classical education – an Honour’s degree from Cambridge –and its irrelevance to the needs of a country, struggling to free itself from the limitations imposed by centuries of foreign dominance. That, he said, was what motivated him to become an accountant, thereafter. When, some months later, I joined the Police Department as a Sub-Inspector, he did not suggest that I was being imprudent. He only said, “Anura, it can be a good career. Just make certain that you have the IGP’s baton in your pocket all the time. You may need it one day”.

Six months later I left the Police and joined George Steuarts as a planter trainee. Twelve years later, when I discussed with him my intention of leaving planting to join the newly established local subsidiary of a foreign production company, he expressed serious misgivings about my choice. I did not heed his advice but a few months on events confirmed his worst apprehensions. However, he was kind enough to facilitate my entry to a highly respected local conglomerate, when, for a number of reasons, my position with my then employer had become untenable. A couple of years later, when I re-joined George Steuarts and eventually became its head of administration and human resources, Scott, as the then Managing Director, became my immediate reporting connection. Despite the deference I always extended to him on all official occasions, he insisted on maintaining an easy friendship. The onus was on me to remember that my friend was also my employer and immediate superior.

Scott was a wonderful traveling companion to places of interest in the country, on account of his encyclopedic knowledge of its history, places, people and, especially, its agriculture, in which he was passionately interested. For him the high points of such trips were the dining stops at humble roadside eateries, where he would wade in to locally made sweets – “Gnana Katha”, a supremely unhealthy combination of sugar and flour, was a favourite, along with oily Chinese rolls of uncertain origin and dubious hygiene – washed down, invariably, with Elephant House Cream Soda, whilst engaging in long conversations with servers and fellow diners in his grammatically precise Sinhala; another contradictory aspect of this multifaceted Cantabrigian. I believe the vernacular was more effective for being delivered in a clipped, British accent!

He was a classicist who became an accountant but who may have been happier as an automobile engineer, or a paddy cultivator in the North Central Province, or a tea grower in the Morawak Korale. In fact, for many years Scott was thus engaged, first with his fifty-acre paddy farm close to Mihintale and, later, with little tea estates in Neluwa and Ingiriya, consecutively. Kannattiya Kele Watte, the paddy farm was, for decades, one of our favourite holiday destinations. In between, there was also a dalliance with a rubber plantation in Kuruwita.

As for Scott’s knowledge of automobile engineering, I have heard him explain precisely, over the phone from his hospital bed to a mechanic perplexed by the intricate electricals of his latest model Citroen, how to carry out a complex repair. A favorite, post-retirement pastime was the buying and restoration of derelict vehicles – invariably Peugeots or Citroens – under his supervision, in the little workshop that he had set up at his home in Pelawatte.

Scott came from a highly conventional, upper middle class Burgher family. He lost his mother when very young and was brought up, largely, by his father Dr. Herbert Dirckze, who retired as Chief Medical Superintendent of Colombo. On his return from Cambridge, he taught briefly at Royal College, Colombo – his old school – before joining Mackwoods, eventually becoming its Head of Finance. In 1964, he joined GS&Co at the invitation of its Board, replacing the retiring Finance Director, John Ferguson. Scott became Managing Director in 1973, when Tony Peries, then Chairman, abruptly left the country, paving the way for Trevor Moy to become the Chairman. Scott became Chairman in 1986, on Moy’s retirement and himself retired in 2001. One of Scott’s greatest disappointments in professional life was that unlike the other Agency Houses, GS&Co was unable to branch out into new businesses early, in preparation for the impending nationalization of large private plantations and the consequent loss of the lucrative estate agency business. Scott attributed this failure, not so much to a lack of foresight, but more to a combination of restrictive historical circumstances and the aversion to both change and risk, on the part of a Board which, till 1964, was entirely British.

Amongst his friends Scott will be remembered best for his unobtrusive generosity to those in need, the deep caring for friends and the meticulously organized, lavish parties at his home, which always represented a bewildering, but enchanting, diversity of cultures, personalities, professions and socio-economic levels. Often, his invitation to a gathering at his home would be qualified by the comment, “the food may be mediocre, but I guarantee that the company will be interesting”.

Scott’s sparkling wit has produced numerous gems over the years. Often, he was the object of his own satire. Some years ago, after he was fitted with a stent on account of a minor cardiac deficiency, I asked whether he was in any physical distress as a result. His immediate reply was, “my dear boy, I felt absolutely no pain till I saw the bill”.

A couple of years before the nationalization of plantations and the threatened state acquisition of other private businesses, a well-known British head of a large commodity broking company made what was then considered, under prevailing circumstances, a rather daring investment. When this was discussed at a gathering at which Scott was present, he had offered the pithy observation, “well gentlemen, I fear he will soon be taken over, “Boss-Stock and Barrel”, sending all present in to paroxysms of laughter; Scott was brilliant at the pun.

He was a totally honest man who despised pretension and hypocrisy. He did not hesitate to expose such in others, irrespective of station, with well-placed, often biting observations. He was always witty, sometimes sardonic but never malicious; acerbic though, if the circumstances warranted, when his razor-sharp tongue would be fully unsheathed.

Notwithstanding Scott’s semi-Victorian upbringing, education and Westernized background, he was passionately Sri Lankan, and a fierce advocate of local products, local innovation, and of the imperative of achieving sustainability through national enterprise.

Till the very end, despite multiple medical complications in the latter years, Scott retained that irrepressible sense of humour, intellectual interest in a disparate array of subjects, the incredibly retentive memory and his concern for fellow men; and, irrespective of the circumstances, he never lost his refined and charming old-world courtesy, another distinctive feature of his personality. In many ways Scott was unique and the last of an ilk, for that ilk died with him.

Some years ago, at the funeral of Abey Ekanayake, a dear mutual friend, as the smoke rose from the funeral pyre Scott turned to me and said, with tears in his eyes, “there goes a very good man; I will miss him very much”. At Scott’s funeral, as the earth tumbled on to the casket, another mutual friend, Nihal Ratnaike, said to me with great sadness, “he was a good and dear friend; I shall miss him very much”. Those are my sentiments as well. I can pay Scott, that fine human being, no greater tribute.