Source:Island

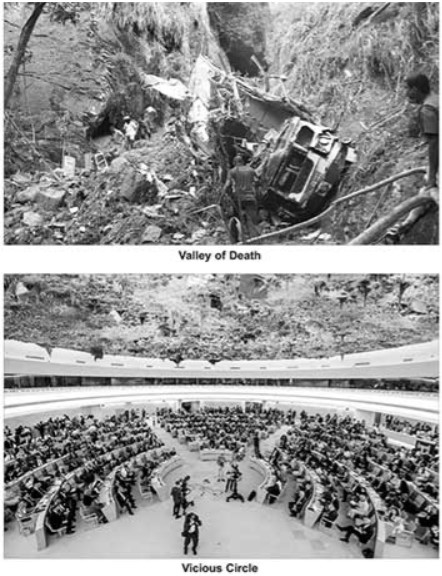

Valley of death in Passara, Vicious circle in Geneva:

Passara was a tragedy caught live on camera. Geneva is where Sri Lanka’s postwar vicious circle makes its annual appearance. It did appear this year and it will be back again come September, then March, and so on. There will be more Passaras and valleys of deaths unless the government stops building new roads to profit some people and starts making old roads safe for all people. Equally, Geneva will be an annual ritual unless the government stops continuing the old war by other means and starts building a new society for everyone to feel equally included.

I am not saying anything new here regarding Geneva and UNHRC, other than paraphrasing the recommendations of the LLRC Commission that Rajapaksa the Elder received with aplomb, and which Rajapaksa the Younger has rejected with disdain. As for Passara, no government worth its name can allow the current situation to go on making road-kills out of sovereign citizens.

Fifteen innocent bus passengers plunged to their death in Passara. Road fatality in Sri Lanka is apparently the worst in South Asia according to media commentaries all of which have cited a 2020 World Bank report for authority. There is nothing in citing the WB report, but isn’t it somewhat odd that international reports are acceptable for road fatalities but they are not for other fatalities that figure in Geneva?

According to the World Bank report about 38,000 road accidents occur every year in Sri Lanka, taking away 3,000 lives and seriously injuring another 8,000. Add them up over 10 to 12 years and the death toll and injury score would be in the same order of magnitude as the number of deaths and injuries during the controversial last stages of the GOSL-LTTE war. Hairs are split about these latter numbers – from Colombo to Geneva to London to New York, pitting Lord Naseby’s numbers against Darusman’s numbers of the dead. The debate is endless and fruitless, because those who swear by one set of numbers will never even consider the other set of numbers. This haggling is over deaths from the past, but there isn’t as much exercising about deaths here and now, that keep occurring and will go on occurring on Sri Lanka’s roads.

Criminal Negligence

Going by reports in the Sri Lankan English media, there were no statements of sympathy or support by senior political or religious leaders after the Passara tragedy. No one of political importance visited the site. Plenty of others have filled in for the missing VIPs. Police spokesperson DIG Ajith Rohana is quoted as blaming that “faulty conditions of vehicles are the root cause for fatal accidents.” So, punish the owner/driver with hefty fines, and fatalities will be reduced. State Minister of Transport Dilum Amunugama has reportedly found a new cause for fatalities – that is allowing lorry drivers with heavy vehicle licences to drive passenger transport vehicles. Now he is about to start a new licensing scheme for passenger bus drivers and make it safe for bus passengers.

There are other theories and remedies that have come afloat after Passara. They include – posting and enforcing speed limits on roads, equipping buses with GPS monitors, to implementing realistic timetables which at present seem to be pressuring drivers to go at reckless speeds. Not enough commentary seems to have transpired over the state of the existing roads and their geometry and capacity to safely accommodate rapidly increasing number of vehicles of different types and different speeds. Speed is not the lone culprit, goes the old traffic wisdom, it is the speed differential between moving vehicles. And poor road conditions create speed differentials and cause collisions.

The road condition on the Lunugala-Passara road would appear to have been the “root cause” of the Passara accident. A boulder and pile of earth that had slid from the slope above was partially blocking the roadway. In the constricted road section on a dual-curve, the ill-fated bus veered off the road while trying to avoid a tipper-truck coming at it in the opposite direction. The Highways Ministry is reportedly trying to determine if there was negligence on the part of a private contractor who had been hired to clear the debris and restore the road. It is negligence alright, and one that should be charged not just to the contractor but to the whole RDA and the area Police. This is what the Daily Mirror said in its March 23 editorial:

“Before the Passara accident a huge boulder had fallen on the road blocking part of it. The lethargy of the officials of the RDA was such that they have not taken steps to remove the boulder for six months despite the road running above a steep precipice. They have not put up road signs either to warn the drivers of the danger. One can find hundreds of such dangerous places in the country, especially in the up-country. The majority of roads in the country are poorly maintained.”

Six Months! Isn’t this criminal negligence?

Six months of criminal negligence have led to the worst accident after the bus-train crash in April 2005 when one of two buses racing each other on the Colombo-Kurunegala road, in Yangalmodara, crashed into a train killing 40 bus passengers and injuring 35 others. Six years earlier in January 1989, a school bus was dragged by a train at another unattended level crossing in Ahungalla, south of Colombo. 41 children and nine others were killed, and 72 people were injured. It was after Ahungala that President Premadasa gave railway officials four days to build gates at 752 unattended level crossings in the country. We do not know how many of the 752 level crossings have been gated since, and no presidential ultimatums have been issued in the wake of Passara.

According to the World Bank report, 10% of annual road fatalities are at level crossings, and, not surprisingly, 70% of road accidents involve low-income passengers and drivers. And the Bank has provided an estimate of USD 2 billion for changes and improvements that would be required to reduce Sri Lanka’s annual road fatalities by 50%. Behavioural (drunk driving, sleeplessness, and speeding), mechanical (failing brakes and bursting tyres), and social (jaywalking, meandering domestic animals) factors play a key role in accidents. But Sri Lanka’s old roads are the primary cause for its high accident toll. And poor road conditions give rise to bad driver behaviour and driving decisions. The estimated USD 2 billion to reduce fatalities is a measure of the physical road improvements that will be required. Not for building new super-highways, but for making old roads safe for the majority of the people who are constrained to travel precariously.

The government should realize from the World Bank estimate of USD 2 billion that upgrading old roads is not only needed to make roads safe and reduce accidents, but it could also be used as a huge economic stimulus – creating opportunities for investment and productive employment. And it would be a far better and socially beneficial stimulus to embark on programme of upgrading old roads, than throwing money on building super-highways – the need for which is never technically established, their environmental impacts are never properly assessed and mitigated, and their costs are never rigorously estimated and adhered to. Is one Passara enough to change the government’s highway-to-highlife approach? How many more Passaras are needed before it can change direction from building new highways to upgrading old roadways?

Resolution and Rejection

There is no road from Passara to Geneva except the pathway through the government of Sri Lanka – from criminal negligence at one end, to diplomatic bungling at the other. The eighth UNHRC resolution on Sri Lanka was passed last week in Geneva. Out of 47 Member Countries, 22 voted in favour, 11 voted against and 14 abstained. The Sri Lankan government officially rejected the resolution first, then interpreted the vote as an implicit victory for its position, and has finally called the resolution “illegal and unwarranted.” What happens between now and next September, and then March 2022 again?

To the extent there have been as many interpretations of the resolution as there have been commentaries on it, it is fair to add one more interpretation and call the resolution as a resolution on the government of Sri Lanka and not on its people. For five years from 2015 to 2019, the previous government of Sri Lanka co-sponsored three UNHRC resolutions, aligning itself with those calling for credible investigations into human rights violations. The present government withdrew from co-sponsorship and is now having resolutions passed against it. What will the government do now? What will the UN Commissioner for Human Rights do now? The claim in India is that the Indian government got the wording of the resolution “tweaked … to say the implementation assistance the United Nations Commissioner for Human Rights will provide must be with Sri Lanka’s “concurrence”.” How will the two – the government of Sri Lanka and the Commissioner, find the elusive concurrence?

Obviously, there is nothing conclusive about either the resolution or the many commentaries about it. At the same time, the resolution and its persistent formulation also indicate that the two extreme desiderata in current Sri Lankan politics are neither sustainable nor achievable. The two extreme desires are, on the one hand, the government’s desire to rescind the resolution and make it disappear for ever and, on the other, the desire among sections of the Tamil diaspora to subject the Sri Lankan government to a form of Nuremberg trial. Neither is going to happen. The real resolution lies somewhere in the middle, and the principal agency for finding it is the government of Sri Lanka. The search for that middle ground is the government’s moral duty, even as saving its people from future Passaras is its prime responsibility. And neither is likely to happen as well.