Source:Island

George Braine in his article “Shakespeare in a takarang shed”, which appeared in the Midweek Review a few weeks ago, referred to Lakdasa Wikkramasinha as being “regarded as perhaps Sri Lanka’s best (poet), writing in English.”

It is painful to admit here that I had never read Lakdasa until then. I scrolled through the web and managed to get a few of his works, and became an immediate convert after reading them. His publications are all out of print, which is not surprising. Books of poetry in English in Sri Lanka usually go out of print very soon after publication. What really surprised me was that they were all very slim booklets and some were private publications undertaken by Lakdasa himself. By the time of his untimely death at the age of 36, any plans he may have had to bring out a collection at some later date died with him.

Assuming that those, who took up the English language seriously, would be familiar with his work, I contacted my friends and relations, who are all serious students of the language. I began to receive a number of his poems. Finally, I contacted Professor Tiru Kandiah in Perth, who very generously arranged for me to access copies of his collection.

I did not find a single of his poems contrived and they were all different. The underlying conflict of his “English” education with his native identity resonated with me. I live in Melbourne trapped by my affection to my sons and grandchildren, yet I sing with poignant intensity Sasara Vasana Thuru, whenever I meet with my old mates here, yearning to be reborn there. Lakdasa writes in English yet manages to flavour the conversation between Iddamalgoda Manike and Ysinno into near Sinhala. He admits proudly his privileged lineage, yet his sensitivity to the disenfranchised and his social consciousness is evident in “The Death of Ashanthi”, which I reproduce below.

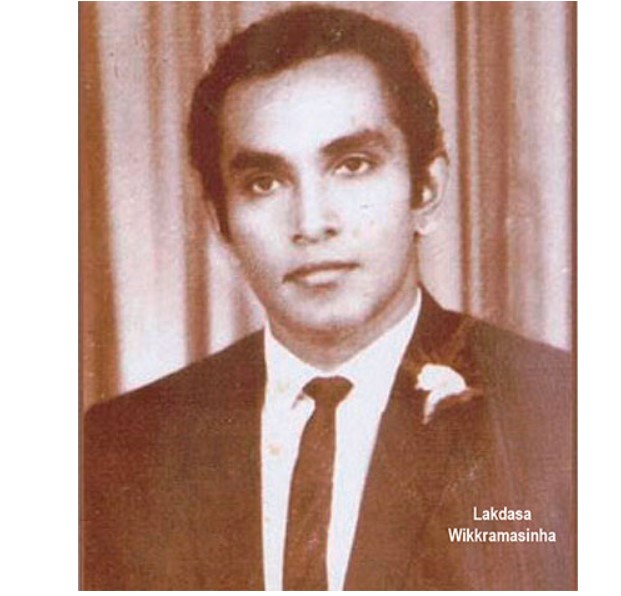

In my youth, I pursued and appreciated the beauty of the abstract in giving mathematical expression to the physical world around us. Mathematics could be considered at the opposite ends of the spectrum to Poetry. Perhaps the four years at Peradeniya, coming under the influence of Sarathchandra and Halpe, the blessings of interactions with others from varied back grounds and a library with a section full of Russian translations, find me like Ysinno with my “lines being not all dead”. For the likes of us, who may have missed Lakdasa Wikkramasinha, he needs to be revived. I wrote to George Braine in search of his poems. Very soon we resolved to bring out an anthology of his works. In his search for a photo of Lakdasa, he found out to our mutual delight that an anthology of Lakdasa’s collected works is in the making. I am so looking forward to it.

In the meantime, I reproduce one of his poems. Any of us who would have had servants would be affected. Any of us who would not squirm at our dismissive attitudes but defend ourselves saying “we treat our servants well”, are not touched by Lakdasa’s poetry. I do not want to analyse his poems as I am not academically competent to do so. Besides, I am afraid that the spectre of Lakdasa Wikkramasinha will visit me and sternly demand to know why I did not allow the reader to be moved by his poem, without obscuring it with a commentary. I consider this simply as a frame, an excuse, an apology, to present a beautiful work as it is.

The death of Ashanthi

A girl I knew her

saw her once or twice eating

or washing the pots & pans, used to sleep

on a campbed in the hall. She was perhaps used

by my cousin: private in the army,

put to look after the pigs (He had a share

in the house being the last male

in the line;) for the sake of blood

I remember I’d nearly married his

epileptic sister (the one who two months back

set fire to the leased-out firewood shed

in the garden one night using kerosine}

Ashanthi was different & I don’t know

how many she’d give herself to

To keep alive –

& a two-year old kid she had; but yesterday

I heard she’d drunk acid, raising a great

marsh howl inside the old house as it burnt

her insides & she dies, a seven-month baby

in her belly; no one even wished to know

who the father was, perhaps there were too many,

perhaps it was my cousin the pig

bearer of a name petering out in such

maledictions. I noticed her earlobes

they were longer than usual as if

gold rings of great intricacy

& weight had hung from them; & then the familiar black stork

danced in the hall

once more, among an army of spines,

an army of men centuries old who watched & gloated

as she lay heaped on my lap, packed

with white seed